As such, the hand-wound chronograph movements of yore remain valued and admired for their robust engineering, practicality and beauty. And, none more so than the movements of the early to mid-20th century.

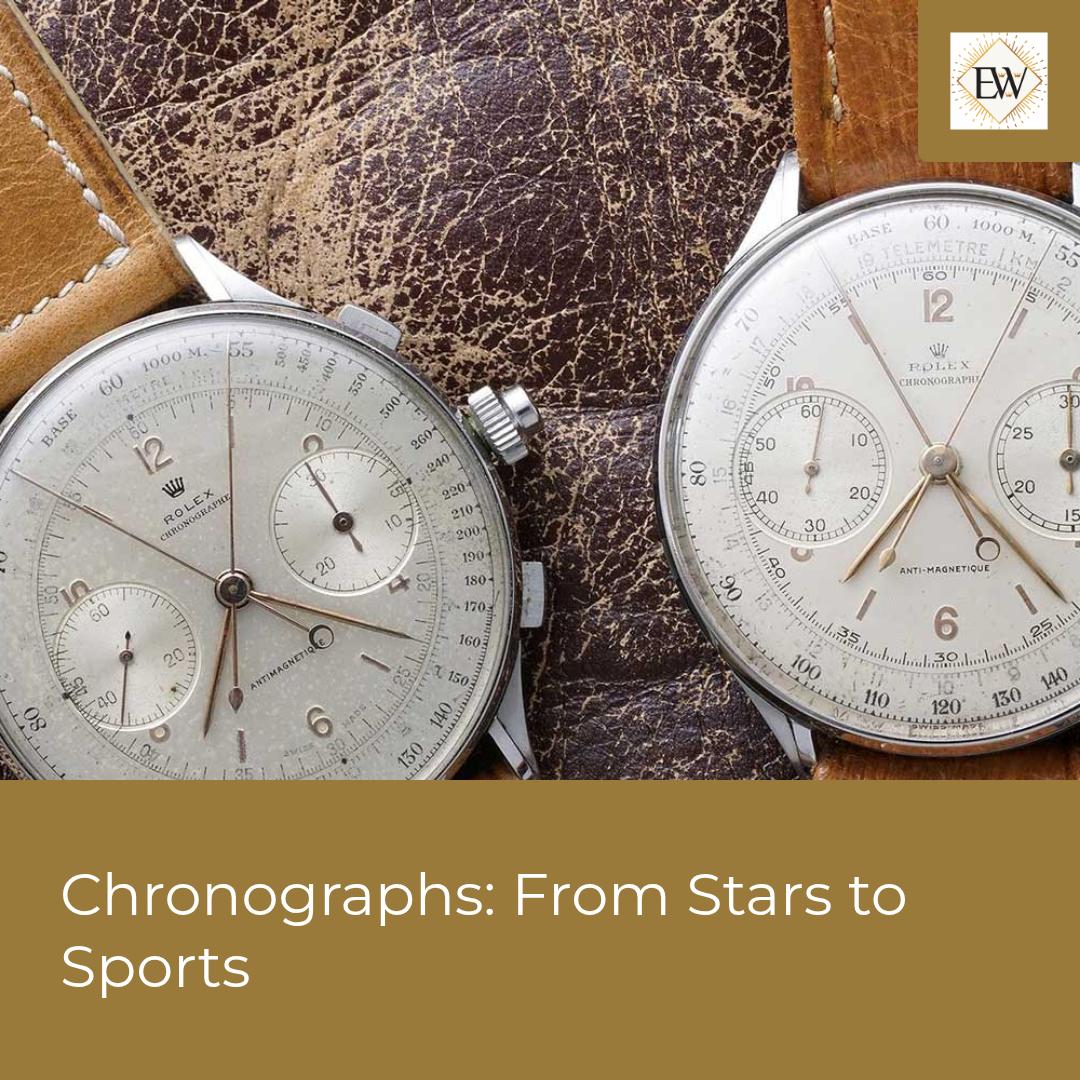

In the decades following the Second World War, classic column-wheel chronographs enjoyed a golden age. In fact, from this period came the watches that are now causing more than the average furore at auction. Up until the Quartz Crisis, it was a norm for brands to utilise the best movements available, with only a few outliers relying on their own production. Many brands, ranging from mid- to high-end including Rolex, Patek Phillippe, Heuer and Breitling relied on the chronograph movements produced by four designated chronograph specialists – Valjoux, Lemania, Venus and Landeron. Though as early as 1940, the latter began producing cam-switched chronographs.

VALJOUX 72, 1938–1974

The year 1938 saw the birth of the Valjoux 72, one of the most vaunted chronograph calibres of all time that powered just about everything, from the Glycine Airman SST to the Rolex Cosmograph Daytona, up until its discontinuation in 1974. At 13 lignes in size, the Valjoux 72 shared the same architecture as the Valjoux 23, which was itself derived from the 14-ligne Valjoux 22 that was originally built for pocket watches.

Like them, it was equipped with a horizontal clutch and a column wheel — a feature that would eventually fall victim to cost-cutting measures across the board. Most crucially, the Valjoux 72 saw the introduction of a 12-hour counter at six o’clock that established what would become the ultimate layout of the chronograph complication.

Other specs include a frequency of 2.5Hz, which was pretty much the standard beat rate prior to the 1960s, yielding an accuracy of 1/5th of a second. These movements would be customised to the specifications of different brands with minor structural modifications and different levels of finishing.

The most notable variant was no doubt the Rolex cal. 72B, or Valjoux 722, found in the Daytona, which replaced the Valjoux 72A found in the ref. 6234. Introduced in 1966, the cal. 72B incorporated a Breguet overcoil and a free-sprung, variable-inertia balance wheel. Subsequently in the late 1960s, the updated 722-1 incorporated a new conveyor spring for the hour wheel to ensure smoother engagement. Many of these movements also featured a metal guard to protect the hairspring from sliding over the stud holder.

And finally in 1969 came the cal. 727, which saw an increased beat rate from 2.5Hz to 3Hz, a modification that was by no means trivial, involving a replacement of approximately 15 components in all.

Beyond these structural modifications, the Valjoux 72 also accommodated calendar complications, presumably thanks to a high-torque mainspring. It acquired a full calendar in 1946 in the 72C used by Doxa, Zodiac, Gallet, Girard- Perregaux among others, culminating in the legendary Rolex “Jean-Claude Killy” triple-calendar chronograph.

At its core, the Valjoux 72 and its equivalents represented an age of two-dimensional chronographs designed with sturdy, flat levers and springs with clutches that operate on a single plane. In contrast to modern chronographs with bridges and levers that are narrow, high and complex, the entire mechanism in the Valjoux 72 is clear and visible at a glance, making it easily adjustable and serviceable, though parts are no doubt scarce today.

LEMANIA 2310/CH 27, 1942–1968

Often pitted against the Valjoux 72 is the Lemania 2310 or CH 27 developed in 1942 as the “27 CHRO C12”. The movement shares the same basic engineering as the Omega cal. 321 used in the Speedmaster that went to the Moon, the cal. CH 27-70 Q in the Patek Philippe ref. 3970 and the later ref. 5070.

The “27 CHRO C12” was a 27mm (12-ligne) column-wheel controlled chronograph with a 12-hour counter. The famed cal. 321 differed from the original 27 CHRO C12 movement primarily in terms of the jumper spring for the minutes.

The latter movement features a robust, single-piece blade- type spring while the cal. 321 was modified to have a complex wire spring and click — a feature that is interestingly absent in the Patek CH 27-70 Q as well as the Vacheron Constantin cal. 1142 found in the Cornes des Vache today. Both of these watches adopted the simpler, single-piece jumper, which perhaps represents a more robust and reliable solution.

And, like the Valjoux 72, the CH 27 had 17 jewels and a frequency of 2.5Hz. The modifications and improvements between derivatives of the CH 27 are endlessly fascinating, with the most impressive version being the Patek CH 27-70 Q. Apart from its obviously superior finishing, it features a fully supported chronograph clutch that pivots over the drive wheel. It is also equipped with the technically superior Gyromax balance wheel as well as a more elaborate kidney-shaped stud holder instead of the simple triangle pinned with a screw on the side.

Like Valjoux, Lemania eventually began creating movements that were cheaper to manufacture and mass- produce. The 2310 was eventually replaced by the cam-switching Lemania 1872 in 1968.

Venus 175/178 FAMILY, 1940S–1960

Among the trio of movement makers, Venus is tragically less famous today for it was never worn by Butch Cassidy, neither has it been to the Moon. But the 175/178 family of chronograph movements leading up to the split seconds 179 and 185 were no less impressive. They were used by scores of now-forgotten brands but most extensively by Breitling. It can be found in many Breitling models from that period including the Top Time, Chronomat, Navitimer, Unitime, Duograph and more.

Produced from 1942 till around 1960, the Venus 175 family had several characteristics that distinguished them from their Valjoux and Lemania counterparts. First, the movement featured a seven-pillar column wheel instead of nine. Fewer pillars ensured a more robust and reliable operation, though having more pillars would mean less rotational force needed and therefore a softer pusher.

Secondly, it also had a drop-hammer design. With a Valjoux specifically, pushing the lower button to reset the chronograph would require a more definite force to push the hammers down onto the heart pieces. In contrast, pushing the reset button on a Venus would instead release the hammer held by a pin that is under the influence of a spring as depressing the start button initially also cocks the hammer. Upon reset, the hammer would then land smoothly on the heart pieces, causing the chronograph to rotate into the zero position.

The family of calibres included the Venus 184 with date, moon phase, and hour counter and the Venus 185, a split seconds chronograph. However, they all shared the same foundation, which was the calibre 175, a 17-jewel chronograph movement with an operating frequency of 2.5Hz. The 175 had two sub-dials while the 178 and beyond had the addition of an hour counter.

In the late 1940s, as demand for cheaper chronographs grew, Venus also began producing cam-switched chronographs – the 188, the 200 and the 210. But as one can imagine, the competition was stiff and Venus sought a financial boost by selling the rights and machinery of their cal. 175 to the Tianjin Watch Factory in China who subsequently upgraded the original 17-jewel movement to their own ST19, a 19-jewel movement, which still remains in production today.

But by the mid 1960s, the popularity of chronographs slowly began to decline due to an increased interest in automatic and waterproof time-only watches. Venus eventually closed its doors in 1966, and its assets were absorbed by rival Valjoux, which discontinued column-wheel production and concentrated on the Venus cam-switched cal. 188, renamed the Valjoux 7730 series.

THE RATTRAPANTE CHRONOGRAPHS

At the very pinnacle of chronographs is the split-seconds, which allows for the measurement of two events that begin simultaneously but conclude at different times.

Mechanically, it is basically a chronograph mechanism but with an additional wheel for the split-seconds stacked on top of the chronograph seconds wheel. This wheel has a spring-loaded lever affixed to it that acts on the heart cam affixed to the chronograph seconds wheel beneath.

When the split-seconds mechanism is activated, the “pincers” around the split-seconds wheel closes in on it, while the chronograph seconds wheel beneath continues to rotate with the heart cam, and the spring-loaded lever rides over the heart cam. Once it is deactivated, the pincers open up, and the split-seconds wheel springs back from the force of this spring-loaded lever onto the heart cam.

The modular nature of the complication would mean that a split-seconds mechanism can be removed from or added on to a base chronograph movement.

Valjoux 55, LATE 1940S–1950S

Considering the rarity and complexity of the complication even by today’s standard, the split seconds chronographs of the mid-20th century were miracles in their own right. And its scarcity in modern watchmaking have no doubt bolstered the appreciation and demand for it on the vintage market. And when brand prestige and rarity come into play, prices are through the roof. Examples include the legendary Rolex 4113 that fetched over CHF 2 million at auction as well as the Universal Genève HA-1 Rattrapante “A. Cairelli” for which prices have shot past CHF 150,000.

Both of these watches were powered by the Valjoux 55, a split seconds version of the Valjoux 54 which was originally conceived for pocket watches. As such, at 39mm (17.3 lignes) in diameter, it was one the largest split seconds movements of that era, making them extremely desirable in modern times.

The Rolex 4113 was the only split-seconds chronograph ever produced by Rolex and moreover only 12 were made. On top of that, the Valjoux 55 in it was also remarkably different from the standard version. It had three pushers instead of two, the top for the split-seconds, the pusher co-axial to the crown for start and stop and the bottom pusher for reset.

Venus 179/185/190 FAMILY, 1940S–1950S

Venus’ expertise in chronographs, on the other hand, culminated in the split seconds calibres 179, 185 (with hour counter), and 190 (with hour counter, date and moonphase) in the 1940s and ’50s. These calibres shared the same basic construction as the Venus 175 with the addition of the split seconds mechanism on top. These movements were used most notably in the Breitling Duograph.

PATEK PHILIPPE 13-130 CCR, 1938–1971

One brand that led the way in rattrapante chronographs, however, was Patek Phillippe. The ref. 1436, produced from 1938 to 1971, was the first serially produced split seconds chronograph by the brand. The movement inside was the 13-130 CCR, which is based on the 13-ligne movement used in the ref. 130 chronograph, itself a heavily modified Valjoux 23.

Because it utilises the framework of the 12-lligne Valjoux 23, the movement is magnificently compact. Some notable modifications include a fully supported chronograph clutch that pivots over the upper fourth wheel, a cap over the column wheel hub as well as the implementation of a swan neck regulator.

The ultimate rattrapante however is the ref. 2571, a split-seconds chronograph and perpetual calendar – the father of the modern-day ref. 5004. It was produced in just three pieces in 1955 and is by far the holy grail of split-seconds chronographs.

THE FLYBACK CHRONOGRAPHS

Some of the most remarkable chronograph movements of the 20th century, with the exception of split-seconds chronographs, however, came from Longines. In 1935, the firm filed a patent for the flyback mechanism, giving rise to the legendary 13ZN in 1936 and its successor, the 30CH in 1947. These movements replaced the Longines 13.33ZN, the first chronograph movement that was not derived from a pocket watch calibre.

Most notably, the 13.33ZN featured an instantaneous jumping minutes recorder, a complex feature found in pocket watch movements that remains exceptionally rare today with two examples being the Datograph and the Patek 5170.

A majority of wristwatch chronographs feature a finger mounted on the chronograph seconds wheel that advances the chronograph minutes every 60 seconds. During which the minute hand moves forward slowly before it jumps to the next minute marker. In contrast, a snail-cam-and-lever system is used in chronographs with an instantaneous-jumping mechanism to ensure a clean and precise jump every 60 seconds. This system eventually gave way to the more cost-effective semi-instantaneous mechanism in the 13ZN and 30CH.

Introduced in 1936, the flyback 13ZN had 17 jewels, a diameter of 29.8mm (13.2 lignes) and height of 6.05 mm. It operated at a frequency of 2.5Hz and was equipped with a Breguet hairspring. For a long time, the 13ZN was believed to be the first chronograph to be equipped with a flyback function, hence its desirability, but it was recently discovered that the function was already incorporated in certain 13.33Zs, which would make the combination of technical qualities in specific 13.33Zs (instantaneous minutes plus flyback function) the most desirable.

One notable variation of the 13ZN is the 13ZN-12, essentially the 13ZN reworked to have a central minute counter. It is believed that only 500 examples of these were produced, making them the rarest variation of the three chronograph movements Longines produced before the discovery of the 13.33Z with a flyback function.

The 13ZN was eventually succeeded by the 30CH in 1947. The movement specifications of the 30CH are nearly identical to the 13ZN except that the layout of the movement is inverted. While the balance wheel in most chronographs is positioned at six o’clock when viewed from the case back, the balance in the 30CH movement is located at 12 o’clock. This is a minor oddity that required a wholesale redesigning of the movement including bridges, wheels and levers.

The clutch wheel for instance encroaches over the balance wheel while the switching works are also inverted. This approach is not unique but more unusual. Apart from having a slightly different pusher feel because the lever to the column wheel is shorter in the CH30, this layout is virtually inconsequential, though it does pique curiosities why Longines would switch to such a construction.

The CH30 was the last in-house chronograph produced by Longines as the demand for low-cost chronographs continued to grow.

THE INTRODUCTION OF THE AUTOMATIC CHRONOGRAPH

By the mid 1960s, there was a pressing need to break out from the conventional operating frequency of 2.5Hz as the threat of quartz resonators loomed large. Fabriques d’Assortiments Réunis (now Nivarox) began developing an improved Swiss lever escapement with 21 teeth instead of 15, known as the Clinergic 21, allowing movements henceforth to operate at a frequency of 4Hz or 5Hz, as opposed to 2.5Hz and 3Hz before. The escapement made its debut in 1966. For a rare insight on this development, read the interview here.

The race to build the world’s first automatic chronograph eventually culminated in 1969. It is worth noting that the seeds of this innovation were planted by Lemania in the 1940s. Five years after the launch of the CH27, the compact chronograph would become the testbed for a “bumper” rotor developed as the CH27 C12 A. Alas, the project was abandoned as superfluous.

The introduction of the first automatic chronograph was a three-way contest between Seiko, a consortium made up of Dubois-Dépraz, Büren, Breitling and Heuer and lastly, Zenith, who in 1960 acquired chronograph specialist Martel. The question of who came up tops is a bit murky, but what’s perhaps more interesting is the unique set of challenges and solutions each movement represented.

SEIKO 6139 SPEED-TIMER, 1969–1979

The Seiko 6139 Speedtimer was the first automatic chronograph to incorporate a vertical clutch – an advanced coupling system that is more complex and superior to the more common horizontal clutch systems of the time, not just in terms of durability but also functionality as it reduces amplitude loss and eliminates the initial stuttering of the seconds hand. To put this accomplishment into perspective, consider that it would take Rolex two more decades to update the Daytona with an automatic movement and it would have to rely on the El Primero (with a horizontal clutch) to do so. It would then take the brand another decade to launch its own automatic movement with a vertical clutch.

Impressively compact, the Seiko 6139 had a diameter of 27.4mm (12.1 Lignes) and a height of 6.5 mm. It had an operating frequency of 3Hz, a ball-borne full rotor, which worked in conjunction with their signature Magic Lever, a compact and efficient bidirectional winding system with a Y-shaped lever and pawl. Alas, the movement went out of production in 1979, which explains why it is relatively unknown in comparison to the other two chronographs of 1969 that have enjoyed a strong following till this day.

“PROJECT 99” CHRONOMATIC/ CALIBER 11, 1969–1970S

The Chronomatic calibre 11 was unveiled by the consortium made up of Dubois-Dépraz, Büren, Breitling and Heuer. It was composed of a lever-and-cam operated Dubois-Dépraz chronograph module 8510 mounted on top an ultra-thin Büren Intramatic movement. Even though the Chronomatic was the only modular chronograph of the three, the Intramatic was itself an accomplishment as it enabled the entire movement to be surprisingly slim despite its modular construction. It measured just 7.7mm high and 31mm (13.75 lignes) wide and had a frequency 2.75Hz along with a power reserve of 42 hours.

ZENITH EL PRIMERO, 1969 – PRESENT

And finally, Zenith introduced the El Primero, the only automatic chronograph with a beat rate of 5Hz, enabling it to measure time with an accuracy of 1/10th of a second thanks to the incorporation of the Clinergic 21 escapement.

The rest is otherwise common knowledge – the El Primero was a fully integrated chronograph with a column wheel and horizontal clutch. Most remarkably, it had a power reserve of 50 hours, which alongside its high balance power, signified a notably well-designed movement that demonstrated an optimal use of space. Conventionally, a lengthened power reserve is often achieved at the expense of balance power.

The legendary workhorse and benchmark for performance, the Valjoux 7750, for instance, strikes a viable balance with a frequency of 4Hz and a power reserve of 44 hours. But the El Primero boasts superior performance on both counts, and manages to be slimmer with a thickness of just 6.5mm versus the 7750’s height of 7.9mm.

It doesn’t take much beyond this to see that the El Primero truly is a great movement, setting the pace for automatic chronographs for a long time to come – till, of course, the introduction of MEMS technology and silicon, which will boost performance on a whole other level.

THE SECOND WAVE OF AUTOMATICS

After the launch of the three automatic chronographs, a second wave of automatic movements followed just as quartz technology was gaining momentum in the horizon.

SEIKO 7017, 1970 – LATE 1970S

Seiko doubled down on its landmark innovation with the introduction of yet another automatic chronograph just a year later – the cal. 7017, a flyback chronograph with a column wheel and vertical clutch. The movement did away with the elapsed minute counter and like the pioneering automatic Seiko 6139, lacked an active running seconds. It was, at its core, a three-hand watch with a zero-reset function.

However, a vertically coupled chronograph movement is particularly fitting for such a design as the lack of a running seconds is a good reason to keep the chronograph seconds running. This is because vertical clutches are of a co-axial structure, which generates friction when the chronograph is not in use as the fourth wheel would be rotating independently. The chronograph seconds can thus serve as the actual running seconds, minimising wear.

As a result of its minimalist construction, the call. 7017 stood just 6.4mm high, significantly slimmer than the 7.9mm of the 6139 just a year before. The cal. 7017 would later acquire a 30-minute counter in the 7018 and a combined minute and hour counter in the cal. 7016.

This family of movements had a frequency of 3Hz, a power reserve of approximately 40 hours and cannot be hand wound.

CITIZEN 8100A/8110A, 1972 – EARLY 1980S

Right on the heels of Seiko was another Japanese watchmaker, Citizen. Introduced in 1972, the caliber 8100A and 8110A represented an advanced class of ultra-thin flyback chronographs that ran at a higher frequency of 4Hz and was able to be wound by hand. The 8100A had a 30-minute counter, while the 8110A saw the addition of a 12-hour totaliser. The 8110A stood at 6.9mm high while the 8100A measured just 5.82mm, making it the slimmest automatic chronograph at the time up until the introduction of the Frederic Piguet 1158.

Lemania 1340, 1972–1975

That year, Lemania developed the cal. 1340 which would be adopted by Omega as the 1040/1041 later. It was a horizontally coupled, cam-switched automatic chronograph movement with an eccentric layout that was redolent of the experimental spirit of the decade. It had centrally-mounted hands for both the chronograph seconds and minutes, which made reading elapsed an intuitive process while freeing up space on the dial for other indications. Located at six o’clock was a 12-hour totaliser while a small seconds counter that doubled as a day and night indicator sat at nine o’clock and a date window at three. Its peculiar design would permeate every other aspect of the watches it inhabited – case in point, the Omega Speedmaster 125 which had an equally distinctive tonneau case and integrated bracelet to match.

The movement ran at a modern frequency of 4Hz and offered a 44-hour power reserve. The key difference between the Lemania 1340 and the Omega 1040 apart from its finishing was that the latter had the addition of a 24-hour indicator in the small seconds at nine o’clock.

The 1040 was Omega’s first automatic chronograph movement while the 1041 was the world’s first the COSC-certified chronograph.

Lemania 5100, 1974 – EARLY 2000S

The Lemania 1340 was eventually replaced by the legendary 5100 in 1974. The dial layouts of both movements are almost identical except that the latter had a separate 24-hour counter at 12 o’clock. However, mechanically, they were worlds apart. This was a movement that was designed in the thick of the Quartz Crisis, which ultimately heralded a perceived need for cost-efficient yet better-performing mechanical movements.

First, it featured a vertical clutch system which made it sufficiently robust for military applications. In contrast to a horizontally coupled chronograph mechanism in which the chronograph seconds is driven by an intermediate wheel, a vertical clutch is typically integrated with the fourth wheel, which directly drives the chronograph seconds. But with that said, it is worth noting that not all vertically coupled chronograph movements have the fourth wheel located near the middle, in which case they would require an indirect train to drive the chronograph seconds.

As a result of having a directly driven chronograph seconds, the 5100 was said to have excellent shock resistance in contrast to horizontally coupled movements of the time wherein the seconds hand was prone to stopping when subject to shocks.

More unusual was its anachronistic, almost perfunctory architecture. The movement plate and bridges were held together by pillars, sandwiching the moving parts. This significantly reduced construction costs as the parts were able to be stamped, as opposed to a conventional movement in which the base plate is milled so as to create recesses to hold all the gears inside. Additionally, parts of the movement such as the column wheel, clutch plate and calendar wheel were made of Delrin, a high-tech, self-lubricating plastic. And instead of a ball-borne rotor used in the 1340, the rotor was seated on a hard iron bearing and held in place with a push fork.

In contrast to its construction, its specs were decidedly advanced. It operated at a frequency of 4Hz and had a 48-hour power reserve.

Valjoux 7750, 1974 – PRESENT

Meanwhile, Valjoux's response to the pioneering automatics was the cal. 7750, a landmark workhorse that would prove indispensable to watchmaking. In many ways, the cal. 7750, like the Lemania 5100, had to be designed with the implications of the crisis in mind. As a result, these movements reflected a distinctly different approach to engineering in which doing the most with the simplest and fewest components was a virtue.

Crucially, the Valjoux 7750 was among the first movements to be built with computer-aided design (CAD) technology, hence various aspects of the transmission system could be optimized to improve performance. It has a notably high-torque mainspring which famously allows it to accommodate a variety of complications from perpetual calendars to tourbillons with no impact on chronometry. Its gear train alone has been continuously adopted and utilised by many brands and in non-chronograph movements due to its robustness and reliability.

Like the Lemania 5100, the Valjoux 7750 uses a switching cam, which, in contrast to a column wheel could be stamped and produced in numbers. But where it differed from many of its ilk is its coupling system. While the 5100 had a more complex vertical clutch, the Valjoux 7750 utilized an oscillating pinion, a highly economical system that consist of an arbour with a pinion on both ends. It is the simplest, most practical way to connect the fourth wheel, which lies on the base plate, to the chronograph seconds above. Because of its small size, it was able to eliminate the sidestep of the seconds hand and minimize amplitude loss when the chronograph is engaged.

While the oscillating pinion was used in the past in movements such as the Venus 170 and the Valjoux 92, it was the Valjoux 7750 that brought it to the forefront of modern chronograph design. After the Quartz Crisis, Valjoux consolidated into ETA, which became part of Swatch Group, and the Valjoux 7750 became the industry’s first stop for an automatic chronograph .

FRÉDÉRIC PIGUET 1185, 1988 – PRESENT

In the years that followed, chronographs became sharp reflections of the seismic changes brought about by the Quartz Crisis. In 1988, Frédéric Piguet unveiled the cal. 1185, an automatic movement replete with upscale features. It had a column-wheel and vertical-clutch design – the most technically superior and costly configuration – along with a ball bearing rotor, a micrometer regulator, and Kif shock absorber. But the movement would prove greater than the sum of its parts.

For a long time, the cal. 1185 stood as the smallest and slimmest automatic column-wheel chronograph, measuring just 26mm in diameter and 5.5mm high as it was based on the hand-wound ultra-thin cal. 1180 that the manufacturer had introduced a year earlier.

This movement is an example of a vertically coupled chronograph in which the fourth wheel is not located in the middle. Instead, its gear train layout is typical of a time-only watch with a small seconds, where the fourth wheel is located at six o’clock. And as such, it is the escape wheel pinion that drives the chronograph seconds wheel in the middle. This construction allows the movement to be more compact. Additionally, its ball-borne rotor accounts for a mere 1.55mm in height.

In terms of performance, it runs at 3Hz and offers a power reserve of 42 hours, which is to say, it is as efficient as its dimensions allow. A year later, the caliber would spawn the world’s first automatic rattrapante, the 1186 which stood at a height of just 6.9mm.

After the manufacture was integrated into Blancpain, the 1185 would continue to find success in and outside of Swatch Group, most notably in the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Chronograph .

Correction March 7, 2022: The Lemania 5100 uses a dual-layer, flat-stamped gear akin to a column wheel and not a cam, as stated in an earlier version of the article.

Original Acritical By Cheryl Chia

We also have a Vintage Watch Guild.

I hope you enjoy all the blogs we have, for the brief history of vintage diving watches Click Here!

Check our Watch Collection Page.

If you are inserted in Selling Watch, Trading Watch, or upgrading your Watch. Please Contact US.